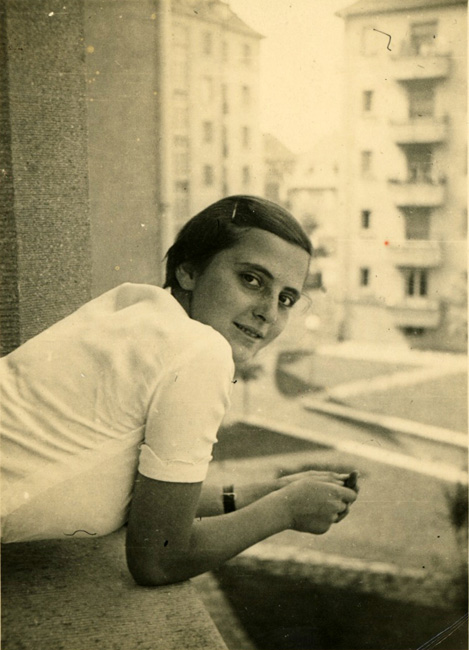

Lore with her mother Lina in 1920.

I was born on May 9, 1920, shortly after the end of the First World War. I lived in the village of Lampertheim-am-Rhein, in a flat, uninteresting part of southwest Germany on the Rhine River. I was a Jewish child.

Lampertheim had a population of about thirteen thousand people. They were trades people, craftsmen, saloonkeepers and semi-retired elderly country people. Lampertheim was a working class community with few professionals, such as teachers, doctors and clergy. Few of its streets were paved. The sandy soil around Lampertheim was good for growing tobacco, white asparagus and red sugar beets.

Lampertheim had a very small Jewish community of about ten families, including some families that had lived there for centuries. Lampertheim’s Jews were not very prosperous and mostly kept to themselves. They were “reformed”—not orthodox—and there was a small synagogue.

When I was born, my family consisted of my father Ludwig, my mother Lina, and my half-sister Erna, who was already seven years old. (Erna and I have the same mother, but our fathers were brothers.) Lina died of a middle-ear infection at the age of 34, when I was just a year old. This was before antibiotics had been discovered.

Lore with her mother Lina in 1920.

I never knew my birth mother, but I know that her maiden name was Karoline (Lina) Dewald; she was born on December 12, 1886; and she grew up in Oppenheim-am-Rhein. Her mother’s name was Lisette. Lina was orphaned when she was young, and then she lived with her mother’s sister, Tante Lina Hecht, in Limburg-an-der-Lahn.

Erna still remembers our mother brushing her long, brown hair and the sound it made. She also remembers mother bathing me in a little bathtub in the kitchen and singing to me not to be afraid. Her memory of mother is of a kind and sweet person.

My father, Ludwig May, was born in Lampertheim on December 25, 1886, the last of six children. Father was a kindly, sensitive man of slight stature whom I felt very close to and who adored me. I can’t remember that he ever raised his voice in anger to anyone. Father was a Kaufman (merchant) and was one of the very respected business people in Lampertheim. People in the community sought him out for advice and counsel.

Father and his older brother Josef owned a small department store, Kaufhaus May, which employed about eight to ten young women. Father was very just and popular among his employees. We lived above the store in a three-story house, one of the largest in the village.

Onkel Josef was disabled. I don’t know what he had, but he was a hunchback. Father and Onkel Josef were very close. Here are father’s remembrances of his brother:

Josef was a very intelligent, self-taught man who accepted his misfortune stoically. However none of the rest of us was allowed to go to secondary school so as not to overshadow him. Josef’s siblings and their children loved him very much, and his purse was always open to satisfy the children’s wishes for small treats.

Many adults—especially the so-called “educated”—made him feel his deformities and looked down on him. He therefore fled to the company of the simple working people—peasants, day workers and mechanics—with whom he gathered every night in the tavern Am Flug. These men respected him. Whenever Josef entered the tavern, the owner would see to it that his customary seat of honor was waiting for him. Whenever an argument couldn’t be resolved among the regulars, all waited for Josef to come and settle it. Here he found strength and recognition.

I remember that father and Onkel Josef had a piece of cardboard near the store’s cash register where they would write down in pencil columns the sales that had been made. And at the end of the day, someone had to add it up. And as a special privilege on a weekend day, I was allowed to add up those columns of numbers. And this was my first real delight in arithmetic that I remember.

Lore with Mutti and baby brother Werner in 1926.

For several years following my mother’s death we had housekeepers who hoped to possibly marry my father. Then father married Ida Roos, a bright young woman from Holzhausen-an-der-Haide, and my younger half-brother Werner was born on March 25, 1926. I was almost six years old by that time and had already developed many of my own ways. My stepmother—whom I called “Mutti” (mommy)—and I didn’t have very much in common. And I think she resented somewhat my closeness to my father. We also had different tastes and feelings. She was interested in clothes and material things, but I was not. I was interested in the outdoors and nature.

Although I never felt close to Mutti, I idolized father, and it was reciprocal. He never raised his voice or scolded me. He loved my fantasies and my passion for social justice. He adored me.

Lore with brother Werner and sister Erna.

Father dreamed of Lampertheim until the last days of his life. In 1958, living in Santiago, Chile, he wrote, “my dreams deal now without exception with Lampertheim. Among those dreams are those of terrible events of the Hitler period which rob me of my breath and my sleep. More dreams still are of pre-Hitler times and present happy pictures and beautiful memories.” Following is father’s short history of the May family:

As seen from existing official documents our family had resided in Lampertheim for over two hundred years. Older records were destroyed in a courthouse fire before that time.

My great-grandfather, Josef May, was born in 1776. He must have been a very frugal man who accumulated some savings. It is told of him—whether it is true or not I do not know—that he built a house. The carpenters urged him to give a roof raising party. After much inner turmoil he donated one bottle of beer. When that had been drunk by the workers, he exclaimed, “God, can they imbibe!”

My grandfather, Mayer May, born in 1807, apparently was just the opposite. His chief occupation was in real estate dealings of farms. There were no railroads then. He traveled high on horse with fine silver spurs. He traveled as far as Saarbrücken. He spent what he earned mostly on himself. He was a proud man. The feeding and education of the five children he left to his wife Hanna. She was by birth an Oppenheimer from Fränkisch-Crumbach in the Odenwald. I didn’t know my grandparents.

The oldest son’s name was Isaak, and he immigrated early to America. I remember that he once came to visit in Lampertheim when I was about five years old. He lived on Sycamore Street in Cincinnati; that is in my memory until today. When we needed affidavits for immigration to the USA, Lore contacted the family through a friend. But they showed absolutely no interest since no contact had been maintained.

The next child was our aunt Mathilde, who married Adolf Stadecker from Worms. As the third child, came our father (Lore’s grandfather) Ferdinand May, who was born on September 4, 1849. Then came a fourth son Bernhard, who died early. The fifth child was our aunt Malchen, who married Simon Retwitzer of Lampertheim.

We were known in Lampertheim only as the Mayers. (Mayer came from our grandfather whose name was Mayer May.) If anyone asked about us as May, people seldom knew who was meant. Our father was called the “black” Mayer in contrast with his brother Bernhard, the “red” Mayer.

My grandfather Ferdinand May died long before I was born, but my grandmother Jettchen May was the center of our family during my entire early life in Germany. Here are father’s remembrances of his home and his parents:

Our house at 79 Wilhelmstrasse was a one-and-a-half story gabled structure that had gone through many architectural changes. At that time our street was called “Hinterdorf” (back village) and the Römerstrasse of today was called “Vorderdorf” (front village). These were the two main streets of Lampertheim.

My mother (Lore’s grandmother) was Jettchen May. Mother’s maiden name was Schwab, and she was born on January 21, 1850, in Rimbach in the Odenwald. She was an orphan and came at age nine to the home of an aunt in Lampertheim, where she worked hard helping to raise seven children. The aunt treated her well.

My parents were happily married and had three sons and three daughters: Johanna (born 1874), Josef (born 1878), Samuel (born 1880), Mina (born 1881), Hilda (born 1885) and myself (born 1886). However they were much depressed because of the deformity and handicaps of my older brother Josef, who was dwarf-like and had a hunchback.

Mother was a very industrious, modest and frugal woman. She was much liked by the helpers and customers in their business. She had to work long hours and save everything she could to accumulate the dowry money needed to marry off her three daughters. She stood from early morning till ten at night in the store and had only one servant to help her with her six children.

My father Ferdinand May was a big, strong, good-looking man with an infectious sense of humor, which only my brothers Josef and Samuel inherited. The rest of us were in looks and temperament like our mother, who suffered greatly because of Josef’s misfortune. Father died of a heart attack in 1908, and mother survived him by thirty-eight tragedy-filled years.

Lore as a young student.

I started school at age six in the village public school, which was near our house. I liked everything at school, and I was a good student. Even though the homes of Lampertheim’s handful of Jewish families were scattered around the village, Jews were never completely integrated into the town. There were very few Jewish children and only one Jewish girl my age with whom I found no bond.

None of our neighbors were Jewish, but I also had non-Jewish friends. Even though my family had lived in that area for hundreds of years, we never were really accepted as citizens. We could tell that people had feelings against us and considered us to be outsiders just because we were Jews and went to a synagogue rather than to a church.

Our family wasn’t very religious, and we didn’t practice much Judaism in our home. When I attended the small synagogue, I didn’t really go with a great feeling of devotion. I was bothered by the hypocrisy and lack of sincerity at the synagogue. Women were segregated from men at that time, and they talked about their clothing. So I didn’t feel there was any real devotion.

From small childhood on, I was a nonconformist and a rebel. I was interested in social justice and equality for all people and never accepted things the way they were. I wanted to change the status of the Jewish community and make Germany more democratic and the town more fair. Also I very much objected to the lesser value that was placed on girls and women than on boys and men. And this I carried with me all through my life. I was a dreamer and wasn’t always realistic. (I think maybe some of my children and grandchildren inherited some of the trait of not accepting things as they are and wanting to change them.)

Germany had been defeated in the First World War and was having great economic difficulties. There was a lot of unemployment, and this helped Hitler to get into power in 1933. Previously the country had been part of an empire, and now it was a republic, but it never really did very well economically. So the time of my childhood was one of great poverty in Germany for the average person.

When I reached the age of ten I began taking the train by myself to a larger community, Worms, to continue my schooling. Eleonorenschule Worms was also a public school, but this one went on to high school. It was an Oberrealschule, which specialized in modern languages.

At first I could eat lunch at the school, but then there came a time when Jewish students were no longer allowed to eat in the school. We had to go to the Jewish section of town and eat there. We felt humiliated by this, but we had no choice.

I remember once I had to write an essay about the difference between genius and Volksbeglücker—a person whose main aim was to cherish and be devoted to the people. This was a kind of hypocrisy, because Hitler was supposed to be that kind of person, and we were essentially being told to have a benevolent view of him.

Lore with brother Werner and sister Erna.

I was not yet 13 years old on January 30, 1933, when Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany by the president, General Paul von Hindenburg. This was the official beginning of the National Socialist (Nazi) government bent of world conquest and rule by terror and murder. Only in 1946, the defeat of Germany in the Second World War ended this dark period.

The night of January 30 is imprinted in my soul as the night the safety of my childhood ended, as I watched with my family in agitated fear the triumphant torch-lit parade of the uniformed storm troopers marching through our town. They ground to a halt in front of our house, shouting “Jude, Jude” (“Jew, Jew”) and painted a Hakenkreuz (swastika) on our wall. This was repeated in front of every Jewish home, not only in our town but all over Germany. It was the birth of the reign of terror. What would tomorrow bring?

The grown-ups should not have been surprised, for the “brownshirts” had for a long time been harassing and beating free-thinking people and causing disturbances. Their hate newspaper was filled with articles accusing Jews of ritually murdering Christian children and was illustrated with caricatures of hook-nosed, fat Jews greedily grabbing moneybags. These hoodlums were now the government.

You have to use your imagination to grasp the extreme conflict in value systems to which I, the child of a liberal, humanitarian Jewish family going to nationalistic German schools, was exposed from early childhood on. Germany had lost the First World War and signed the Treaty of Versailles, ending its status as an empire and making it a republic. Inflation and unemployment were rampant. Democratic values, held high in homes like mine, were never really honored and taught in the schools of the new Weimar Republic. Emperors, kings and queens were still idolized in the history texts as noble national heroes. The Treaty of Versailles was referred to as the “shame treaty,” and wide-eyed, passionate little girls like myself were under the hypnotic spell of the repeated message of the schools to restore at personal sacrifice the lost glory of the Empire.

I had friends—both Jewish and non-Jewish—who had very nationalistic feelings at that time, and we believed that Hindenburg was a great hero. I wasn’t really aware of his close relation to Hitler and how he helped the Nazis get into power. I had a photograph of Hindenburg on my night table and kissed him every night before going to sleep.

My best friends were Aryan (Nazi terminology for pure-raced) classmates from old guard, anti-democratic homes. Among our patriotic fantasies was to run away from home and set on fire the palace near Paris where the Treaty of Versailles had been signed and to thus become patriotic martyrs. I was not aware that my intended sacrifice would never be accepted because I was Jewish

Needless to say, my father was alarmed and distressed about my wrong-placed reactionary loyalties. He thought I would outgrow them as I became more mature. He believed in the gentleness of my nature but was too depressed and preoccupied by the dangerous direction of German politics to see the psychological dangers this nationalistic fervor presented for his impressionable daughter.

Lore at the age 13 in 1933.

The first time I was arrested was when I was 13 years old. I was rehearsing a speaking chorus with other Jewish children to perform for a festival in the synagogue. It had to do with hateful acts against Jews in Russia dating back to the First World War and had nothing at all to do with Germany. As the chorus ended, it said, “We pledge to break the chains that so shamefully hold us bound. We are the youth of the New World.”

Well, I had loaned my big geometry book to a non-Jewish student who had lost hers. She was a poor student, and I was trying to help her. But she found a copy of this chorus in my book. She gave it to a teacher who was also the leader of the Hitler women’s organization and said, “Look, I found something against the Third Reich,” which is what they called that period after the Nazis came into power in 1933. And here it was in my geometry book.

So while I was in school in Worms, the Gestapo (secret police) went to my parents’ home in Lampertheim and searched the house for other evidence of a conspiracy. But they didn’t find anything at all. So then the Gestapo came into the school and asked the principal to let me go with them to their headquarters in order to be interviewed about what I was up to and what I had done, where I had gotten all of this stuff. But the principal was a very decent man and said, “I’m not going to let a thirteen-year-old child go with you to the Gestapo headquarters. If you want to interview her, you have to interview her right here in school in my presence. It’s my job to protect her.”

So they interviewed me there, and the principal lost his job because of that. He was fired because he didn’t conform to what the Gestapo wanted him to do. And the funny part about it, the young girl whom I had given my book to, who found this writing, she belonged to the Hitler Youth girls’ organization, and she thought it was her sacred duty to expose a traitor. And there I was trying to help her out of not getting a reprimand for having lost her book. So it didn’t take very long before I was in trouble. And this is only one of many, many times this kind of thing happened to me. I continued to have trouble in school until they finally kicked me out.

I was then almost 15 and began going by train to Mannheim, a larger, more modern nearby town and continue in a girls’ high school, Elisabethschule Mannheim. I went there for a while, but it got so bad politically, especially for Jewish children, that I had to leave. I had to listen to talks about the fact that Jews had smaller brains than non-Jews and were inferior. And they measured the circumference of my head and the heads of all the other Jewish students to try to prove that there wasn’t enough room to adequately house a well-developed brain, and that’s why Jews were closer to apes than to human beings. It became so bad in that school that I found it intolerable to continue there. So I was last in school at the age of 15.

After that, whatever I learned, I taught myself. Mannheim had a castle with a large collection of things from Egypt, so I would spend time in the castle studying about ancient Egypt. And I went to the art museums and the libraries and studied about art—all of this without being in school. Sometimes my parents didn’t even know I was doing these things.

I spoke about the fact that I was always rebellious. I belonged to an organization of Jewish youth, and the leader of that organization was an Eastern European man. He was quite a bit older than I was. And most of the people within the organization had backgrounds from eastern Germany, Russia and Poland—not western Germany, like my family. Jews from western Germany thought of themselves as assimilated into the German culture—as Germans of Jewish religion and stock and not as Jews who lived in Germany. They owned land, lived among the other Germans, attended the same schools, had the same occupations, and spoke the same language.

Jews from western Germany were very, very proud and arrogant and thought less of these people from Eastern Europe who had lived in ghettos and had been educated in separate schools, whose foods, dress, occupations and Yiddish language distinguished them from their surrounding populations. And my family shared that arrogance. But I didn’t.

So without my parents knowing, I would visit the homes of these Eastern Europeans and was very close to the leader’s sister, who was dying of tuberculosis, a disease that you could easily catch. And I would visit her at her bedside to keep her company. And so I was always doing things that felt very important to me but which I tried to cover up and not let my parents know about.

My rebelliousness was making life unsafe for my mother and father, so the only thing for them to do was to get me out of Germany as soon as possible. They didn’t want to leave, because they had old parents there and a handicapped brother who hadn’t yet been killed by the Nazis—but who was a little bit later. My father just didn’t want to leave these old people alone. And yet I made it so difficult for them.

I wanted to go to Israel—which was called Palestine at the time—to live on a kibbutz, which is a collective farm where people live in a just society rather than in a capitalist system. But my sister Erna was already living in the United States, and my parents wanted their children to be together. So for the safety of my parents, I had no choice but to take the route to the United States.

Lore on her way to America in 1938.

So on January 8, 1938, at the age of 17, I went by train from my hometown to Kehl, a town on the Rhine River, which divides Germany from France. Kehl is on the German side, and Strasbourg is on the French side. The police had confiscated my passport in order to make it hard for me to leave and had said they were going to return it to me at the French border.

So I was on the train without a passport, without any documents, and just ten Deutchen Reichsmarken—the equivalent of four American dollars—and I was very scared. Then some German officials came onto the train at the French border and asked for papers from all the people. And I had none, so they weren’t going to let me continue on. They took me off the train and searched me, trying to find if maybe I had some hidden currency I was trying to smuggle out of the country. They looked inside the soles of my shoes and everyplace else and tried to keep me from getting on that train and getting across to France.

In Kehl, a French crew replaced the German crew to cross the Rhine River to Strasbourg, and the passengers told them that the Germans had taken a young girl off the train and they were worried because she hadn’t come back. So the French crew said they were not going to cross over the Rhine into France until this young girl who had been taken off the train came back. And it was because of that that I got from Kehl into Strasbourg without a passport or anything.

In Strasbourg, I was embraced by the open and loving arms of the Hanaus—my father’s sister Tante Mina, Onkel Victor, Fe, and Otto—who gave my sadness a much needed pause. From Strasbourg, I went via Paris to Le Havre, France, where I took a ship across the ocean to New York. The trip at that time took about a week.

I was able to immigrate to the United States because of a wealthy uncle—Jacob Dewald, the brother of my real mother—whom I had never met before and who had left Germany as a young man. He signed an affidavit promising to support me and to never allow me to become a burden to the United States.

When I arrived in the United States, I expected to find a picture I had in my mind of little Trinity Church, which is a church near Wall Street in New York, being squashed by Wall Street skyscrapers. That meant that capitalist exploitation and money-grabbing were thwarting the little church, which was a symbol of spiritual life and human rights. This is the way I expected the United States to be. I had a feeling that there was no justice, and nobody was interested in anything except making money.

Well, I was very lucky when I arrived in New York. At first I lived in a rooming house with my sister Erna. And then a young woman, Yvonne Blumenthal, who is still the closest friend of both my sister and me, invited me to live with her family in their mansion near West End Avenue as a kind of daughter—even though I had no money whatsoever. And sometimes I was taken to school by their chauffeur. So my first home was with this wonderful family who were Jewish, but who also were among the founders of the Ethical Culture Society. And this helped me to make a very easy transition.

I knew I wanted to study, but I had had so little high school—so little education, really—and I hardly spoke any English. I lived with my sister, and from February to June 1938 she paid for my going to a training school run by the Ethical Culture Society. But I didn’t particularly like what I was studying there, because it was for people who wanted to teach kindergarten and I was interested in more advanced education.

One day, a girl whom I had become very friendly with left, and I asked where she had gone, and they told me she left to go to Columbia University. And I asked where that was, and somebody told me. So I took the buses and went there. And I asked, “Who is in charge of this school?” And they told me the president was Nicholas Murray Butler. And so I said, “Well, I’ll try to find him.” And I found the way to his office and told his secretary I wanted to see Nicholas Murray Butler. But she asked, “Do you have an appointment?” And I said, “No.” And she said, “You have to have an appointment.” And I said, “Well, I’ll just wait.” And so I just sat there and waited.

Finally, one of the times when the president came out of his office, he said, “That girl is still here. What does she want?” And the secretary said, “She doesn’t speak very much English, but she said she has to see you. She won’t talk to anybody else.” So he told me to come in. I said, “I hear you have a very good school. I’m not learning enough where I’m going. I haven’t gone to a high school and I’m all self-educated, but I’d just like to give it a try. How do I get in?” And he said, “Well, I don’t really know what to do, but we have an experimental part of Teachers College, and I’ll call somebody who is in charge.” So he called a Dr. Tewksbury, and said, “I have a young girl sitting here and she won’t leave. But she wants to have a good education. Would you listen to her and do what you can?”

I found out later that this was the first time in all the years Dr. Tewksbury had been in charge of this part of the Columbia that he had gotten a personal call from the president of the university. He must have thought, “If the president sends somebody here, it must be important and I’m supposed to do something to help.” And he did. I told him that I didn’t know much English and didn’t have any money, but I wanted a better school and would work hard. My English wasn’t even good enough for them to give me an entrance examination. He said, “I’ll let you stay and register, and then in a few months we’ll see if you know enough English to take an exam.”

So I was given temporary admittance to New College, which was an experimental part of Columbia’s Teachers College. Eventually they gave me a scholarship and did away with the entrance examination, because I understood what was going on in my classes. Two of my favorite instructors were Leo Huberman, who later started the socialist Monthly Review, and Morris Mitchell, the Quaker economist. So I started at Columbia University at age 18 without having finished high school—simply because I was so interested in getting a good education.

While I was beginning my new life in the United States, my family back in Germany struggled for survival during the Nazi regime. In April 1938, three months after I escaped, my father was forced to sell his business for a pittance, and in June the family fled to the relative safety of an apartment in Mannheim owned by a British citizen who was Jewish. Because father had so many dependents in Germany—his mother, his handicapped brother, and some other persecuted Jews—he felt the family couldn’t leave them behind just to look after themselves. So they stayed. And when my family finally had no choice but to leave they couldn’t get exit papers to join my sister and me in the United States. It was very difficult to get into the United States, and they had nobody to sponsor them.

Finally, through some acquaintances, they were able to get papers to be admitted to Chile, where they had not expected to go. Father, mother, and my younger brother were on the North Sea when the Second World War broke out. So they lived in Chile for the rest of their lives.

Other relatives weren’t so fortunate. Many of my aunts, uncles and cousins were resettled, and there was no way of staying in touch with them. Father’s sister Hilda, her husband Ferdinand, and their son Fritz were removed to Gurs, which was a resettlement camp in the Pyrenees mountains near France’s border with Spain. From there they were deported by railroad to Auschwitz concentration camp in southern Poland. And when they arrived at Auschwitz they were all exterminated in the gas oven. But in the German methodical way they made a list of the occupants of that railroad car with their names, birthdays, hometowns and occupations. And later my cousin Fe Hanau, who lived in France, found the documentation that shows what happened to them.

The Nazis said my uncle Josef was “shot and killed while trying to escape” from Buchenwald concentration camp. But there was no way that he could try to escape, because he could barely walk. So this was just a subterfuge to kill him because he was just too crippled. After a payment of 30 Marks, an urn with his ashes was sent to grandmother, who died just over a year later.

I only stayed at Columbia for one semester, from September 1938 to February 1939, because I found out that the university was doing things to court the Germans under Hitler and had even sent somebody to a festivity given by the Nazis at Heidelberg University. I was very disgusted and revolted against this, and I didn’t want to have anything to do with Columbia if they flirted with the Germans for some kind of gain. I wanted to leave, regardless of what they had done for me.

So in February 1939, one of my professors, Morris Mitchell, who was a pacifist and could understand my feelings, accompanied me on the train to Illinois. He introduced me to Dean Bennett at the University of Illinois and saw to it that I got accepted.

Rabbi Abram Sachar, who was a professor of religion at the University of Illinois—and who later founded Brandeis University—took me on like a daughter and sponsored me for a scholarship that the Hillel Foundation gave, and it was through that that I could attend the University of Illinois without having any money.

Rabbi Sachar also introduced me to Phi Sigma Sigma, a Jewish sorority on campus, where I had a free room in exchange for some duties, including tutoring other girls to help them pass their tests. I still remember going through initiation when I had to answer the telephone by reciting some foolish verses. One day Morris Mitchell was attending a conference at Chicago, and he called the sorority house to see how I was getting along. I answered the phone with, “Hoity-toity, my fair beauty, I’m only here to do my duty. If with a member you want to chin, Tell me her name and I’ll see if she’s in.” After hearing this, Morris responded, “I think I had better get you out of that sorority as soon as possible!”

The University of Illinois gave me credit for all the classes I had taken at the Ethical Culture School and at New College. I took a very full course load at Illinois, with up to 21 units in a semester, and I passed eleven courses by examination. In this way I was able to receive my undergraduate degree in October 1940 after three semesters and a summer at Illinois. This was only two and a half years after I had arrived in the United States without a high school education and hardly speaking English.

I majored in elementary education so that I could become a teacher of teachers—and that’s what I became. In the fall of 1939, I enrolled in a criminology class. And that was how I met Don, who was my professor. We become good friends and finally married on June 4, 1940, when I was twenty.

Lore and Don on their honeymoon in 1940.

It was January 1938 when I left Germany with a little suitcase and ten Deutchen Reichsmarken (four American dollars). I was alone, not allowed to be accompanied by any adult, seventeen years old, and told to take a Nazi-determined train from Mannheim to Kehl-Strasbourg, where on the French side (Strasbourg) I was embraced by the open and loving arms of the Hanaus—Tante Minna, Onkel Victor, Fe and Otto—who gave my fear and sadness a much needed pause. (For you, my children, I will write some other time about the horrors of that train ride. What I am now sharing with you is a literal translation of the letter I sent to my German-reading family and the Aryan (non-Jewish German) friends I made [on my return visit to Germany in February 1984].

So on with the translation:

What happened in Germany and Lampertheim between the years 1933 and 1938—and what turned out to be only the early horrors—I do not need to describe to those who will read these pages. Those of you who are still alive will always have in your deepest souls the terrible grief, despair, and misery of these years. You all had to leave behind most intimate family members—brothers, sisters, fathers, mothers, uncles, aunts, cousins, nephews and friends—tortured and murdered. These losses will live with all of us as long as we are alive. Add to that the loss of our homeland, unsere Heimat, and the unprepared need to try to form roots in an unknown environment. For us “young ones” it was possible—not so for all of the generation of our parents.

I was seventeen years old at the time. Never did I return to Europe/Germany. Only once did I get for a few weeks as far as England. I could hardly bear to hear Germany/Lampertheim even mentioned. I have tried to burn them out of my memory. My life, so I believed for over forty years, had only its beginning in America. There I was made a part of the loving circle of the Rasmussen family. What remained of the old life was the love of my parents and siblings in the new life. For forty-four years I have had Don Rasmussen at my side and already for a long time three extraordinary sons, Peter, David, and Steven, and since then in addition ten grandchildren.

Already for a long time have Don and the children pleaded with me to record details and memories of my childhood. Professional life and the sad shadow that was cast for me over my youth kept me from doing so.

It was really the heartfelt invitation of Ferdinand (Fe) Hanau and his wife Eve to visit them in Paris (Fe is Anne’s brother) and Anne Hanau Prower and Don’s encouragement that gave me finally the resolve to do so. Don, who is most of the time wise, believed that I should make this trip alone so that I, without consideration for him and without having to translate for him, would have a chance to let my innermost private feelings guide me to find the proofs of a childhood that I had so long suppressed. Much time to change my decision to go he did not give me. He almost “forced” me to call Fe in Paris and to announce that I would be at his door in two to three weeks.

So I traveled on the tenth of February 1984 in typical Rasmussen style. That meant cheaply, adventurously, not using the simplest routes. I flew on Icelandair from New York directly to Luxembourg, took an included train from Luxembourg to Paris the next day, and only knew that I would have to catch a return flight from Luxembourg to Reykjavik, Iceland, on the twenty-third of February and after two days there return to New York and then Philadelphia. (What actually happened was that by courtesy of the airline and overbooking, I had an extra day and then returned via Chicago to Baltimore and by taxi, paid by the airline, to our home in Philadelphia.)

I knew when I left that perhaps I would have the courage when once in Paris to travel on to Mannheim–Worms–Lampertheim and then take the free airline express bus back to the Luxembourg airport. I really did not know why I wanted to visit Lampertheim. Perhaps it was because I wanted to visit the grave of my mother again, for from earliest childhood I remembered that Mutti (Ida) would go with me there in order for me to put down on the empty gravesite a stone. This stone somehow was to signal to my mother, angel in Heaven, that I visited her. Perhaps I wanted to rewalk the roads and paths and alleys of my childhood. The most important of those were to grandma’s house on Wilhelmstrasse, to my primary schools (the old schoolhouse and the new), to the railroad station, to the Kirmis (a festival) near the Catholic church, and to the Holland, a little brook where I often at dawn rode on my bike before I took the train to school and where I would sit under a willow tree and unburden my heart in improvised poetry. (Often I stopped for a moment on the way to the Weber’s house.)

I wanted to see the Kaiserhof where Onkel Joseph “lived” with his buddies toward evening, having just one Stein (beer) at the Stammtisch (table reserved for regulars). This was his only private life outside the circle of his family (us) that he allowed himself. (Onkel Joseph, an older brother of my father, was a hunchback, a wonderful uncle to have and a dear, dear man the Nazis tortured and murdered.) I wanted to see the house of my birth. Did I really want to? I don’t know.

In Worms I wanted perhaps to see my former school but also the Judengasse, far away, where after Hitler I had to eat lunch, for we Jewish children were no longer allowed to eat in school. (It was in that school where at age thirteen and a half the Gestapo (secret police) came to arrest me, but that is another story.)

In Mannheim I wanted to see the castle where I spent many, many hours of many days—without the knowledge or permission of my parents. They believed I was in—after my arrest I had to leave school in Worms and continue in Mannheim—but school had become a too cruel place for Jewish pupils, and I sought peace and wonder in the Egyptian division of the castle library.

But, most of all, I wanted to visit no one, only use again roads, paths, ways—slowly—in order to awaken again the old thoughts and feelings of Childhood and Youth and make them real and true for now.

The nine days with Fe and Eve in Paris were important, content-rich days. Only once did I see briefly Fe since the forty-six years when he accompanied me from Strasbourg to Paris and perhaps to the boat in Le Havre. What had become of me, the delicate, naive, dreamy girl, in the meantime? What had become of him, my charming, warmhearted, older cousin, through war, flight, hiding, and then his newfound family life, in the circle of his wife, three children, sixteen grandchildren? Would we be able to reestablish the connections (ties) of the past? We didn’t even then really know one another too well. The difference of our ages was too great. But for my part I found out that “blood is thicker than water.” (I don’t remember if there is such a German proverb.) He can’t possibly know how much joy he gave me when he said a few times, “It must be that we are related for we have so many of the same interests and Weltanschauung!”

Fe and Eve were such good hosts and were so natural that I felt very much at home and not at all in the way. We have to repeat that either in Canada or Paris! Fe reminded me of Don in his type of humor, and Eve, just as I, hasn’t yet learned to be prepared for the tricks played on us.

Because Fe spent already many years on the researching and writing of his family history (mainly his father’s; his mother is my father’s sister), I have learned many new things about the May family. He showed me many documents which Mr. Karb, historian of Lampertheim, sent him (Fe sent me copies of some) which prove that the Mays (sometimes earlier called Mayer) have lived in Lampertheim at least since 1740. I know, and Werner confirms it, that Onkel Joseph showed me a much earlier letter of an ancestor’s dealings with a Hessian Lord in whose service he was.

It was Fe who encouraged me to travel on to Germany by myself. I took a morning train via Saarbrücken (where the Hanau family once lived) to Mannheim. I left my heavy suitcase in a locker there, made reservations in a traveler’s hotel for the following night, and went on by train to Worms, the beautiful historic little town where I stopped in a simple railroad hotel. Then I walked around in this lovely Roman-time city. Worms had now even more charm than years ago but unlike Mannheim had not changed much or been destroyed by war. I had only time to walk around in the historic section and visit the Judengasse past the cathedral and to stop at the historic synagogue destroyed by the Nazis but faithfully reconstructed. The next morning while still dark I took a bus to Lampertheim. Hardly any trains make that route now. One needs to change trains for what used to be a half-hour trip.

In the half hour that I was in Mannheim I found the telephone number of Oskar Althausen in the telephone book. (He was about my age in Lampertheim, and we were well acquainted. He was Jewish also.) I called him with the only ten-pfennig coin I had. Should he have been surprised or glad to so suddenly hear my voice after forty-six years, I wouldn’t have known. It turned out that he had no time to see me the night I was staying in Mannheim before riding to Luxembourg. I did learn from him whom I needed to contact to get into the Jewish cemetery in Lampertheim. No Jews live there now. So in the dark, on a rainy morning, I arrived in Lampertheim, Hessen. I had a “stone in my chest” and I felt very lonely. I asked the driver to let me off at the railroad station so that I could enter the town as I had when coming daily home from school from age ten on. I went into the station and looked for a locker for my overnight bag but couldn’t find one. So I went to the ticket window, the exact same ticket window of over fifty years ago where I always bought my monthly ticket to take the train to school!! The lady there told me she would keep my bag in the luggage place. She lifted the same heavy door as she would have done fifty years ago!! Nothing, but nothing, at the Lampertheim Bahnhof had changed!! I was so happy. That was almost the only place where my time had stood still for over half a century.

So now I am on the way to Kaiserstrasse (where I lived) via Ernst Ludwig Strasse, but without my big chestnut trees. I had really counted on finding my beautiful trees again! I could still recognize some of the well-kept, neat homes on the way, the homes of long-ago owners—friend or foe—I knew.

I walked slowly in the rain, deep in thought. How much shorter the street now seemed to be to the courthouse and the Kaiserhof, both still recognizable, as also was the house my cousins Ullmann used to live in and where my big doll broke on the steps and where now there is a bank. Our house is more or less unchanged but without a balcony. Where yard and garden used to be there is now a parking lot. It is a bank also. I was not at all moved by seeing the house, and I didn’t enter.

Then I noticed that the Röhrigs still had a business across the street from my former home. It is now much, much bigger and more elegant, selling gift articles and coins besides the stationary and printing shop of former days. Their house is now two stories high and modern. I entered the store. Why I decided to, I do not know. I first hesitated several seconds, for I couldn’t remember what the political position of the Röhrig family had been during my family’s last Hitler years in Lampertheim.

A woman greeted me, expecting me to be a customer. I asked her if any of the Röhrig family were still alive, that I was born across the street sixty-four years ago, and that this was my first return in forty-six years. She disappeared, and another woman, about my age, came with open arms toward me, hugged me, and said, “You must be Lore May. I am Anneli Röhrig (now Kahle)! Do you remember me? I must be six or seven years younger than you. Tell me all about your whole family. What a joy to see you, what a joy. Have you had breakfast? Have a cup of coffee with us.” Still not comfortable and at ease, I could not accept the invitation. I had planned earlier to seek out the bakery and coffee shop Schmerker and eat breakfast there. It was to be sort of a pilgrimage, for I remembered how decent that baker was during the shunning of Jews, and how at night in the dark he brought bread to Jewish homes. Anneli told me that neither the old baker nor his baker son were still alive, and a daughter-in-law who would not know that story now owned the business. Still I wanted to go there after I had finished with my walking tour of the past. I promised Anneli to return towards noon in order to say good-bye.

Anneli inquired, before I left on my search for familiar landmarks, if there was somebody, somebody I had a longing to see again. Without hesitation I answered that my greatest childhood love, even now still near to my heart, had been Maria Weber, who as long as I can remember had been employed in my father’s store. Anneli made a few phone calls, then handed me the receiver—and there on the other end of the line was Maria Weber Linz in Stollhofen-Rheinmünster in the Black Forest.

We were both so astonished and happy and both cried. She asked by name about the whole family, and we reaffirmed our still existing mutual love for one another. She told me that for all these years she has thought of me on the ninth of May, my birthday, and sent me every year her love. She is now seventy-eight years old and a widow, lives alone, and takes care of a shop she owns.

When I put the receiver down I could not believe that I had really made such a deep contact with my childhood. I didn’t know how to thank Anneli for doing something so loving!!

Then I went to walk. There is not much to tell about that. All of a sudden the roads (passages) and buildings were no longer so important, for I had found clear, true human love.

Grandmother’s house no longer exists; the house of the Süss family (now in Chile) I couldn’t find because a road was closed for construction. I went to the cemetery and left my little stone. The grave of my mother is still there, but her name is hardly readable. I found also grandfather’s grave (Ferdinand May), a commemorative tablet built in the wall in honor of the Jewish soldiers who died in World War I. Uncle Samuel’s name (Erna’s father) was among them. A large monument had been erected in remembrance of the Jewish martyrs of Lampertheim of the Hitler period. None of my photos turned out. It was too dark in the rain.

Then I went to the Schmerker Cafe for breakfast. I ate in silence like a sleepwalker. I left with the waitress a card for the owner in which I wrote her that I came to eat in honor of her parents-in-law, a very small tribute to pay.

Then I went back to see Anneli to say good-bye and to take a train back to Mannheim. But from that point on unexpected events began.

Anneli and her husband awaited me with excited tension. They had worked out a surprise for me. If I wanted, I would be picked up in three-quarters of an hour by Maria’s sister Anna Weber Schäfer, her sister-in-law Gertrud Weber (widow of Martin Weber), and her son Christoph. They would all drive me to Tante Maria’s house in Stollhofen and then from there at night directly to my hotel in Mannheim. But first I must eat lunch with Anneli while Mr. Kahle would retrieve my overnight bag from the station. So I ate with Anneli. During the meal we spoke freely, and I met her youngest daughter who is in teacher training. Anneli’s oldest daughter, now a gynecologist, spent a few years ago six months in a kibbutz in Israel, and then the director of the kibbutz was Anneli’s house guest in Lampertheim for a week. Anneli and her husband had also made a trip to Israel, and their daughter arranged a tour of the country. Only Jews were on that tour. And it was deeply moving to hear Anneli tell with tears how emotional an experience that had been. To begin with, being the only Germans and the only non-Jews, they were treated with distrust and suspicion. By the end of the week they parted as good friends. (I have tears in my eyes as I write this.)

And there I was, Lore, and had hesitated a bit to even enter the Röhrig’s business!

I left with beautiful presents—a child’s history book of Lampertheim, picture postcards, a book of etchings of the Biedensand made by Lehrer Lepper, a friend of father’s. Thank you, Anneli! You understood quickly how to heal much of my pain!

So at 13:00 we start our car trip to the Black Forest. Christoph, young, intelligent, very warmhearted, is the driver. He just happened to have come home that day for vacation from Mainz. There he studies theology at the Guthenberg University. He has a sister who is married to an obstetrician and lives in Lampertheim. Ana Weber Schäfer is a widow too. She had to sell her bakery and now raises the children of her son who lives with her. She is affectionate just as I remember her. Her life has also not been easy. Both her brother Martin and her husband never joined the Nazi party because of their Catholic faith. They got many beatings, but they served as German soldiers in World War II.

With the fine car and the excellent expressway we arrived in Stollhofen rather quickly. I remember the same distance (to Baden-Baden) as a daylong trip! Sisters Anna and Maria hadn’t seen one another since October. “Tante Maria” is a very active, fast-moving woman, rooted in the earth, unbelievable for her age. I get a welcome as if I were the high point of her life and I immediately feel as if I were “home” and surrounded by love. That love is pure and deep; one can relax in it. We sit together till dark and talk, talk, talk. Maria is the storyteller and questioner, and the others mostly listen. But they are included in the family intimacy, and we are all aware of that. Maria and Anna are touched by my memory that Werner, as a baby who would not eat, stayed with their mother for six weeks and got well.

Maria told me much of my mother. She knew her well since she started to work for my father at age sixteen. She remembers when my mother told her that she was pregnant with me. She helped my mother decorate my basket in lilac colored silk. She was there when I was born. She helped my mother bathe me. With sadness she remembers the morning my mother called her to bathe me alone while she supervised and watched. She felt weak, and it was the beginning of the illness that a week later cost her life (middle ear infection?). For bathing me she got a big chocolate bar of the finest quality. She also told me about the parade of housekeepers who took care of me before Mutti’s (Ida’s) arrival; one of them was a mean police-type who hated children. Onkel Joseph often sent Maria upstairs from the store to be his spy and report how I was treated.

Maria and Anna worshipped our father and Onkel Joseph. They seemed still proud to have had such honorable, fair “Chefs.” Yes, she also spoke much about the life-loving little Erna who did as she pleased regardless of consequences and about the too well behaving Lore, easily intimidated.

We had refreshments, coffee, rolls, cheese and sausage and pastry and sweets in Maria’s old peasant house with its nineteenth-century-type store. I toured the whole house and saw Maria’s bedroom furniture, which she proudly announced was from Kaufhaus May. In the wonderful store I received a dozen beautiful handkerchiefs as a good-bye present and in return gave as gift the promise to come again and stay a few days.

After a photo session we left for Mannheim at sundown with glistening snow on the mountains.

In Mannheim Christoph dragged my heavy suitcase to my hotel room and all three came for another visit with me. After a final “Auf Wiedersehen” I had to separate myself from my old-new friends. The next morning I rode by bus to Luxembourg.

That, what weighed heavily on me for forty-six years, like the pressure of the Alps (Alpendruck), that, what I feared, turned into an intimate, significant experience through the bonds with really honorable families, the Röhrig-Kahles and the Webers.

On April 27, 1984, I received a long letter from Oskar. He was so sorry not to meet me. He wrote to Chile and got my address, and now I will write back to him.

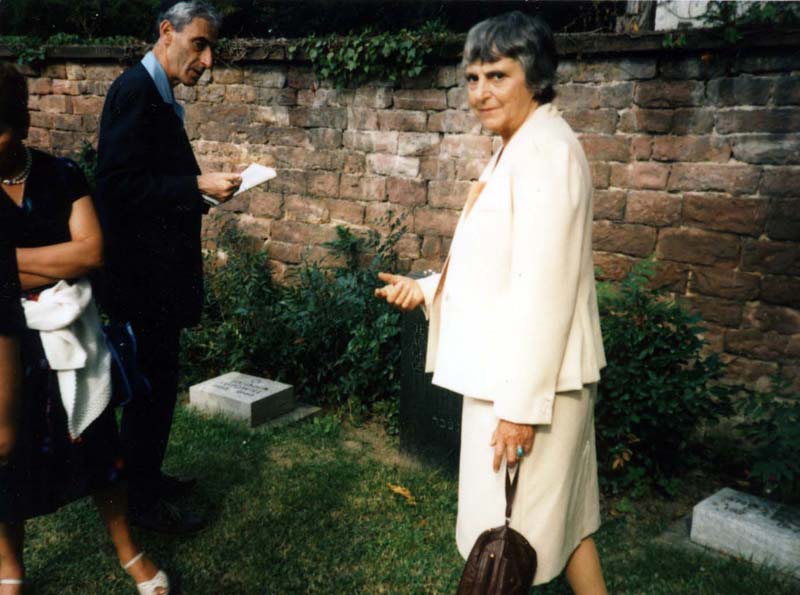

Lore and brother Werner visit their grandmother’s grave in 1984.